Government Report Indicates Robust Foreign Investment Review in Canada

The Canadian government recently released the 2021-2022 Annual Report covering non-cultural 1 foreign investment reviews under the Investment Canada Act (ICA) from April 1, 2021 through March 31, 2022. Given the government’s reluctance to publicize details of its ICA reviews, the Annual Report is a key resource for gaining insight into the way the ICA is being enforced in practice.

Overall, the Annual Report confirms a return to pre-pandemic levels of foreign investment in Canada, with a rebound in the number of “net benefit” reviews tracking closely to pre-COVID averages and continued consolidation of the government’s national security review jurisdiction. These factors are illustrated by a sustained increase in the number of investments being subjected to enhanced national security screening; signs of an increasing diversity in outcomes, including a substantial number of scrutinized investments being permitted to proceed without further action; as well as a material number of investments being withdrawn voluntarily in the face of increased scrutiny.

Below are highlights and key points from the Annual Report regarding the ICA’s two review processes: (i) net benefit and (ii) national security.

Net Benefit Review

The ICA’s net benefit review process obliges a foreign investor to apply for government approval for any acquisition of control of a Canadian business that exceeds certain thresholds. If those thresholds are not exceeded, the investor’s only obligation is to advise the government of the transaction by filing a “notification” at any time up to 30 days after closing. A similar notification obligation applies when a foreign investor establishes a new business in Canada.

Record number of total filings. The 2021-22 period saw the highest number ever of net benefit filings for investments to establish or acquire control of (non-cultural) Canadian businesses. All told, foreign investors submitted 1,255 filings under the ICA in 2021 22 – up 52% from the 826 filings made in 2020-21 (when global investment flows were still suffering from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic), and also higher (by about 22%) than the year prior to the pandemic (1,023 filings were made in 2019-20). It may be noted, however, that the extent of compliance with the ICA notification obligation is unclear, and compliance may be improving as consequences of a failure to notify increase, such as the extended exposure to a national security review, as discussed below.

Net benefit reviews return to prior levels but remain infrequent. Only eight of the non-cultural ICA filings made in 2021-22 were applications for review relating to acquisitions of control for which government approval was required; the remainder (1,247) were notifications for investments for which no approval was required. Consistent with typical practice under the ICA, all the applications for review were approved as being of net benefit to Canada. Although the Annual Report provides no details, we can assume that all eight of these transactions were approved on the customary basis of the investor providing binding undertakings regarding matters such as future investment in the target Canadian business, maintaining minimum levels of employment, and Canadian participation in management, among other commitments.

The eight net benefit reviews in 2021-22 represent a rebound from the low of three such reviews in 2020-21, and that number is more consistent with recent experience (e.g., there were nine net benefit reviews in each of the three years before 2020-21). Overall, however, the number of net benefit reviews remains much lower in absolute terms than only five years ago (there were 22 applications for review in 2016-17), reflecting the cumulative impact of increases in financial thresholds for net benefit reviews first introduced in 2009. Indeed, net benefit reviews have markedly declined as a percentage of total filings over time: from 2.99% in 2016-17 to 1.20% in 2017-18 to now only 0.72% of all filings in 2021-22.

Duration of reviews has increased. Interestingly, despite the relative decline in the number of net benefit reviews conducted annually, the time required by the government to complete such reviews has increased. For example, the median review period for net benefit reviews in 2021-22 was 88 days, up from 77 days in 2020-21, 76 days in 2019-20 and 64 days in 2018-19. It is difficult to draw firm conclusions from this increase in review time frames, which can often be influenced by non-substantive factors, like ministerial availability; however, the increase in national security scrutiny of investments (discussed below) may be placing a strain on agency resources, including with respect to the processing of net benefit applications.

National Security Review

Under the ICA’s national security review regime, the Canadian government can review all foreign investments in Canadian businesses – regardless of value or degree of control – to determine if they could be “injurious” to Canadian national security. If the government identifies national security issues, it may prohibit the investment from proceeding, order the Canadian business to be divested (if closing has already occurred) or permit the investment to proceed with conditions that the investor must agree to or abandon the transaction.

All investments for which ICA filings are made under the net benefit regime are screened for potential national security concerns. In addition, investments that may not be subject to the net benefit regime may also be scrutinized (e.g., when the foreign investor acquires a minority interest in, but not control of, the Canadian business).

Robust national security enforcement continues. Twelve investments were subject to a formal national security review in 2021-22, which is the highest number for such reviews in a single year. Seven of these investments were allowed to proceed unconditionally following completion of the review; four of the investments were abandoned after the formal review was commenced; and one review is ongoing with the outcome still unknown.

An additional 12 investments were the subject of an extended initial screening process of 90 days (the screening process takes 45 days if not extended) but did not proceed to formal reviews. Of these 12 investments, nine were allowed to proceed unconditionally without undergoing a formal review, and three investments were abandoned after the investor was advised that a formal review might be commenced.

Two observations are noteworthy. First, there has been a steady increase in the number of investments allowed to proceed unconditionally at the end of a formal national security review, to the point where most (7 out of 11) of the formal reviews completed in 2021-22 had this result. This means that it is no longer inevitable (or nearly inevitable) that investors’ acquisitions will be blocked, unwound or burdened with conditions at the end of the national security review process.

Second, the number of investments that are abandoned when a national security review is commenced – or even threatened – remains high. This happened in 7 of the 24 cases in 2021 22, in which investors were told that they would or could face national security scrutiny. Perhaps this attitude will change if the number and percentage of investments that are ultimately allowed to proceed unconditionally persist.

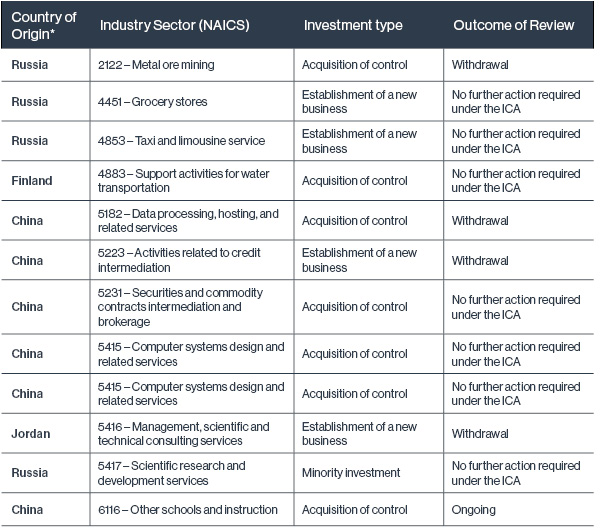

Targets of reviews. One of the most useful aspects of the Annual Report is that it provides some details of the investments that were subject to formal national security review.

*The Country of Origin reflects the country of the ultimate controller of the investor.

Source: Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada.

The above table confirms that the jurisdiction of the investor remains a key factor in determining whether a transaction may be subject to formal national security review. Chinese (six) and Russian (four) investments accounted for 10 of the 12 investments subjected to a formal national security review in 2021-22. The one matter still undergoing review also involves an acquisition of control by a Chinese investor. The other transactions subject to formal reviews in 2021-22 involved investors from Finland and Jordan, indicating that investors from the “usual suspect” countries are not the only ones that get caught up in the national security review process.

Recent developments may foreshadow an even less favourable outlook for Chinese and Russian investors in the future. As discussed in more detail below, the government has introduced policies that make it more difficult for investors with Russian ties to acquire interests in Canadian businesses and for foreign state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to invest in Canadian companies involved in the critical minerals sector (an area of particular interest for Chinese investors). Indeed, based on these new policies, it is unclear whether certain investments that were allowed to proceed in 2021-22 would necessarily pass national security muster today (e.g., the three Russian investments for which no further action was required).

The industry sectors that attracted scrutiny are also noteworthy. Some of these are obvious – for example, metal ore mining, data processing, computer systems design and scientific research and development services. But other sectors are not so obvious – for example, grocery stores, taxi and limousine services, and “schools and instruction.” This diverse range of sectors underscores the discretionary and even unpredictable nature of the ICA national security review process.

Finally, it is clear that not only acquisitions of control may lead to the initiation of formal national security reviews. Minority investments and the establishment of new businesses also feature among the investments caught in 2021-22 (the latter category accounting for one-third of the reviews).

Duration of national security reviews. According to the Annual Report, the average duration of national security reviews in 2021-22 was 133 days. On the face of it, this seems much lower than the average duration in previous years. For example, formal reviews took an average of 225 days to complete in 2020-21 and 217 days in 2019-20. Three factors seem to explain this discrepancy (none of which suggest a sudden increase in government efficiency). First, unlike in previous years, the average review time calculation includes not only formal national security reviews but also transactions that were subject to only enhanced initial screening, which involves a structurally shorter process. Second, all the reviews completed in 2021-22 involved either withdrawals by the investors before those reviews were completed (or perhaps even started) or approvals without conditions. Third, the 133 day average does not take into account the review that is ongoing. We believe that the average duration of more complicated reviews is likely closer to the averages of the past two years – that is, the duration is likely to exceed 200 days, at a minimum.

Looking Ahead

We turn away from the parameters of the Annual Report to recap here several recent developments that signal national security issues will gain even greater prominence in the coming year.

Voluntary notification regime introduced. In August 2022, the government issued new regulations permitting foreign investors to voluntarily submit notifications regarding minority investments in Canadian businesses that are not otherwise subject to mandatory notification under the ICA.

One purpose was to give these investors the opportunity to obtain pre-closing comfort that their investments are not of national security concern. However, the other purpose was to enhance the reporting of investments with potential national security implications that might otherwise have escaped the government’s attention. The government reinforced this second objective by also providing that investments that are not notified may be subject to national security review for a full five years after implementation. Although it is still too early to tell, this “voluntary” regime may result in a further increase in filings under the ICA and potentially an increase in the number of transactions subject to national security review.

New policy statements. The government issued two new policy statements in 2022 that signal a tougher approach to national security reviews in certain circumstances.

On March 8, 2022, the government issued a policy statement regarding the review of Russian investments in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Specifically, as we discussed in more detail here, the policy provides that all investments from Russia (whether or not connected to the Russian state) that are subject to net benefit review under the ICA will be approved only on “an exceptional basis”; furthermore, all investments that have “ties, direct or indirect, to an individual or entity associated with, controlled by or subject to influence by the Russian state” will provide grounds for a full and formal national security review under the ICA.

Similarly, a new policy governing investments by SOEs in Canada’s critical minerals sector was announced on October 28, 2022. As discussed in this bulletin, this policy provides that foreign SOEs and related parties investing in Canadian critical minerals businesses will be able to obtain net benefit approval only “on an exceptional basis” where such approval may be required; and they can further expect to face a full national security review for any such investments.

Canada’s New Indo-Pacific Strategy may lead to ICA amendments. The government's Indo-Pacific Strategy announced on November 27, 2022 contains relatively blunt statements about the potential national security threats posed by China and outlines plans to strengthen Canada’s defence against foreign interference, including by "reviewing, modernizing and adding new provisions” to the ICA to protect national interests and “acting decisively” when investments by SOEs and other foreign entities threaten national security, including critical minerals supply chains. While any potential changes to the ICA are not yet clear, they may relate to certain priorities referred to in the strategy, such as protecting Canadian intellectual property and research, and preserving Canada's cyber security systems.

More transparency. The government has announced that it intends to change its policies regarding the publication of details about its national security reviews. As noted previously, the government has, up to now, been very circumspect in saying anything publicly about its national security reviews, including whether such reviews have even been commenced. That is why the limited disclosure in the Annual Reports has been so important. However, the government has now changed its approach and announced that it will make public the results of national security reviews that led to a remedial order being issued. Just recently, the government did this when it blocked three investments by Chinese investors in Canadian companies active in the critical minerals sector. One by-product of this new transparency will be to heighten public attention and interest regarding the government’s enforcement of the ICA’s national security review process. Another by-product may be the continued inclination of some investors to withdraw investments before the completion of formal national security reviews that may appear headed for remedies, and thereby side-step the potential for negative publicity.

The Annual Report, coupled with these other developments, underscores that foreign investors must remain aware of the ICA’s review processes – and the national security regime above all – in their transaction planning when considering investments in Canada.

1 The Annual Report deals only with ICA filings made with respect to foreign investments in “non-cultural” businesses. These are subject to the authority of the Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED). Investments in Canadian businesses involved in “cultural” activities – such as book, film and video production and distribution – are subject to the authority of the Minister of Canadian Heritage and are not covered by the Annual Report.